SESYNC was founded with a commitment to accelerate socio-environmental (S-E) discovery by providing extensive and flexible support to diverse teams throughout the life cycle of their research projects. This support varied depending on researchers’ unique needs but included advice on proposal development, matchmaking across disciplines, team-meeting facilitation, provision of cyber infrastructure, data science training, and much more (“the SESYNC process”). SESYNC also committed to an informal experimentation process for team synthesis with an openness toward integrating innovations that may improve the process.

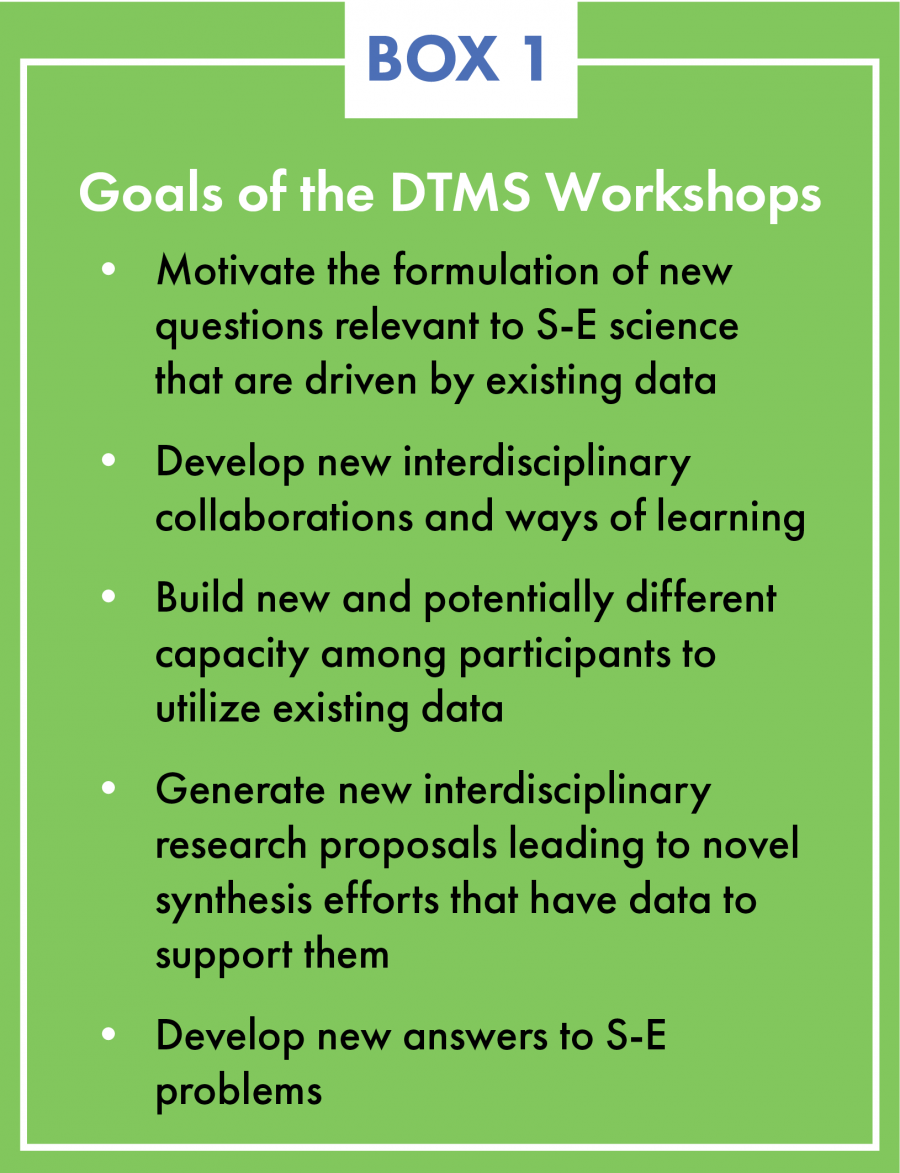

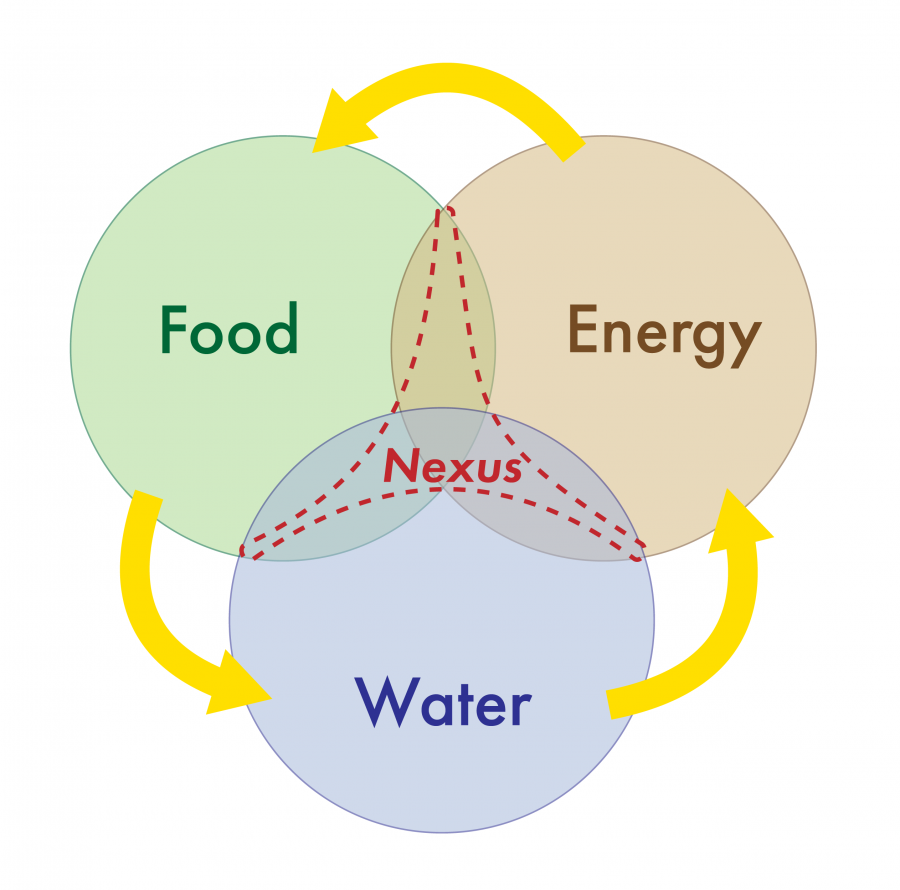

The Data to Motivate Synthesis (DTMS) project is one example of this experimentation. The project focused on developing both data discovery infrastructure and a facilitated team-building process that could accelerate interdisciplinary collaboration. Three-day workshops brought together disciplinarily diverse groups of early-career scholars who had not previously collaborated. The workshops’ topical theme was the Food-Energy-Water (FEW) nexus, which is of interest to a broad array of scholars and can be conceptualized through many different frameworks. In addition, the FEW nexus was a focus of multiple federal agencies that participated in the development of the DTMS approach and infrastructure.

|

Image

|

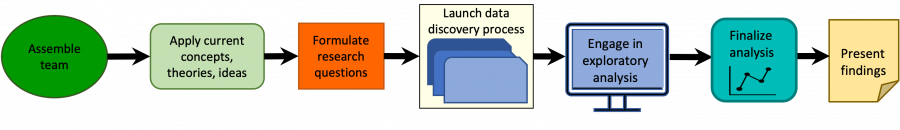

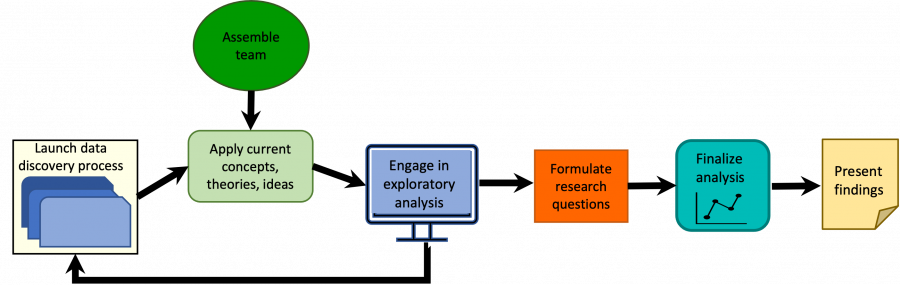

The classic model for team research is a linear process spearheaded by a few individuals.

Synthesis research typically follows the well-known path of one or two scholars articulating a question, identifying additional team members, gathering needed data, and undertaking analysis. This approach has generated many important insights; however, it is often the case that the research questions must be changed or end up going unanswered because of data limitations. Additionally, the data that the team seeks, the research questions themselves, and how the team approaches those questions, reflect the leaders’ disciplines rather than the full scope of the research problem, different disciplinary perspectives, or different ways of exploring the questions.

SESYNC asked, “What if we flip the synthesis approach?”

What if data discovery occurred first and then novel interdisciplinary teams formed based on interest in a problem and awareness of existing data that could illuminate that problem? A team could then co-identify the exact questions to address in the context of data availability and the diverse disciplinary perspectives and methods of their team members. To encourage this approach, SESYNC's DTMS workshop leaders began the meeting with an introduction to a cyber platform developed by SESYNC that allowed individuals to explore specific topics and available data related to the FEW nexus.

The three-day workshop process used a process analogous to the “sandpit” approach that was first tested in 2009 by federal funding agencies in the UK. SESYNC’s goal was to bring people together who would not normally interact and facilitate a process to encourages development of interdisciplinary research ideas and team formation based on shared topical interests.

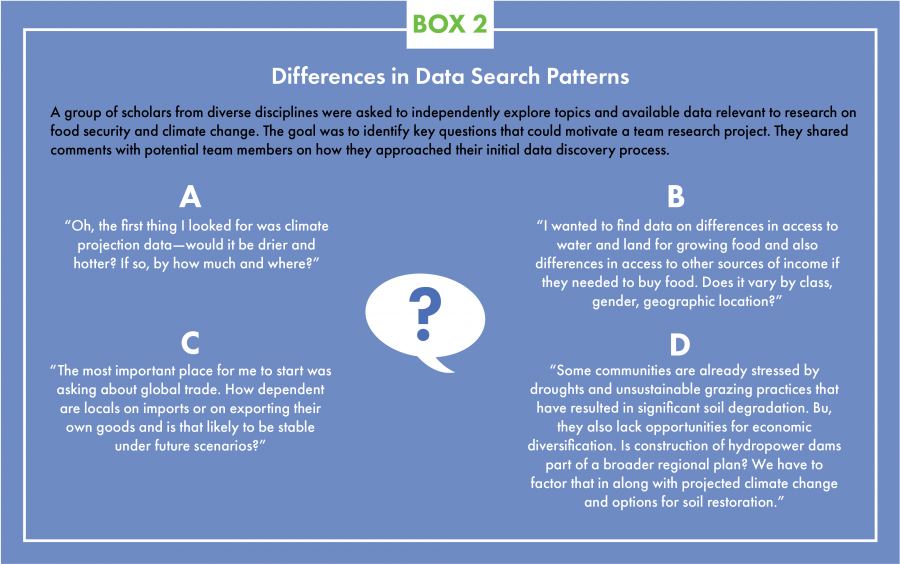

Participants were allowed to move back and forth from working alone to working together to discover data and refine questions of interest that they could potentially answer with those data. After participants worked individually to discover data using the cyber platform, a facilitated group discussion focused on how each person approached data discovery—what topics and data they explored, in what order, and why? This exercise revealed differences in the assumptions, values, and perspectives that participants brought to a broad problem such as those illustrated in the fictional example in Box 2. Such differences arose not only due to the diverse life experiences of individuals but often due to their disciplinary training.

The cyber platform as a boundary object

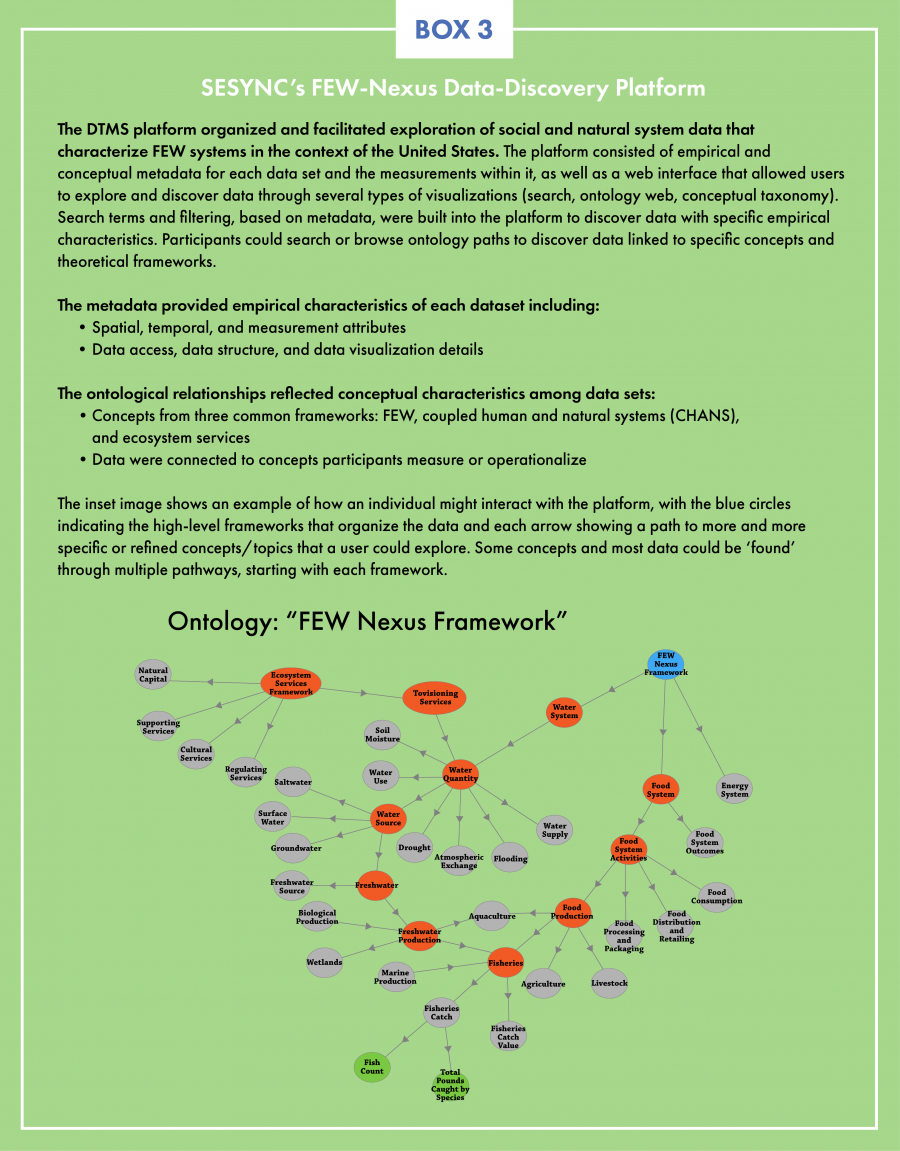

To facilitate the flipped process—data discovery to question formulation and team formation—SESYNC staff and collaborators built a digital platform that included three distinct approaches to data discovery. Accessed through a single user interface, the participants could 1) search for data and concepts using keywords, 2) explore the conceptual relationships among data using a visualization (maps) of ontologies (a graphical network or “hypertree,” Figure 1) that organizes data and associated concepts from various analytical approaches, and 3) compare characteristics of the data such a their measurement units, to identify integration opportunities and challenges. The platform enabled participants to discover metadata from roughly 300 publicly available datasets, mostly focused on North America, and users could move among the three discovery approaches as they moved through the data discovery and collaboration process.

Using the keyword approach, participants could search for data of interest and could refine the search results by further filtering on empirical metadata characteristics like temporal or spatial extent or resolution. Using the data ontology that was developed to reflect common frameworks used to study socio-environmental systems, participants could discover data representing variables that are often studied together by socio-environmental researchers. The data ontology organized the concepts in a hierarchical network, so that users could move from high-level concepts (like the food system or the water system) to more precise concepts that could be measured empirically (for example, production of grain crops). The ontology included nodes for data sets and measurements within the data sets, so users could discover data that measures specific concepts and how those measurements are conceptually connected. The ontology structure was depicted in two ways in the DTMS interface, as a graphical network map through which users can move to visualize linkages among data and concepts (Box 3), and as a hierarchical list (much like a taxonomy) that presents the linear paths from high-level concepts to specific data.

Like any boundary object, the DTMS cyber platform created a context that facilitated the sharing and integration of knowledge. Because each person used the same platform but queried it in different ways, then shared how they did that and why, the process promoted conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge—allowing diverse participants to communicate through cross-boundary discussion.

What are DTMS' outcomes and future?

During its lifetime, SESYNC was only able to host three DTMS workshops before the COVID-19 pandemic ended our ability to host in-person meetings. Thus, no formal assessment of the effectiveness in facilitating novel teams and science was possible. Pre- and post-workshop surveys of participant reactions did indicate that afterwards they were more likely to use secondary data in research and much more likely to use that data’s associated metadata to determine feasibility of answering specific research questions. Several SESYNC working group proposals did come from new collaborations formed from DTMS workshop participation. The DTMS platform is not publicly available and was not feasible as a permanent online tool, mostly because of the critical role that SESYNC facilitators played in the workshop, as well as the importance of face-to-face interactions.