For a downloadable PDF of this Explainer, click below:

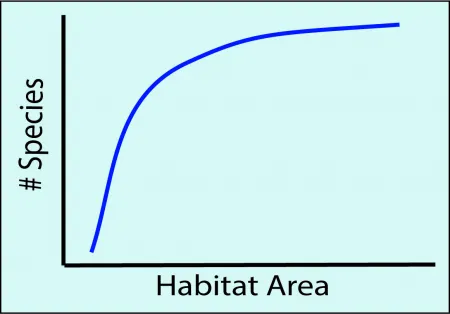

Since the earliest days of ecology, scholars have recognized that space matters. But it was not until 1997 that the phrase spatial ecology was first coined (Tilman and Kareiva 1997). The distribution of ecological elements and processes across landscapes, in water bodies, and ocean floors influences the distribution of species, their interactions and access to resources. We know from years of ecological research that the amount of habitat and its diversity (habitat heterogeneity) are important ecologically (Figure 1)—not only to biodiversity, but also to abundances, material flows, and the energy passed through food webs.

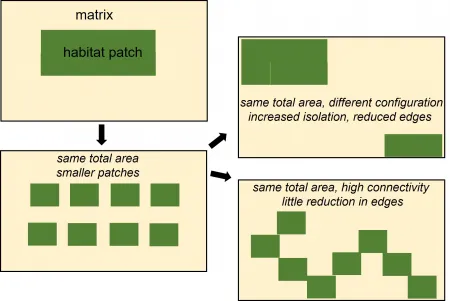

Additionally, Tilman, Kareiva, and others have shown, that it is not just the amount or type of tree cover or seagrass habitat that matters—it is how the pieces of nature are clustered. Their arrangement can be highly fragmented into similar patches or a combination of different types of patches (“mosaics”). The distance between them may vary. Patches, such as, pieces of land with different plant species, parcels of soil with different physical and chemical characteristics, and riffles vs. ponds within a stream may be contiguous (touching), could be randomly spaced, or even be over-dispersed on the land or water scape. These different patterns in spatial distributions influence what thrives where, foraging patterns of animals, the flow of propagules or water, and of course where humans have planted crops. The field of spatial ecology is closely related to many other branches or conceptual frameworks in ecology including landscape ecology, island biogeography, meta-ecology, and movement ecology.

Landscape ecology

The most well-known of these frameworks is the field of landscape ecology. While often focusing on large scale topics like deforestation, landscape ecology is fundamentally the study of spatial heterogeneity and how that influences species and flows of materials such as propagules, water, and nutrients (Turner and Gardner 2015). Extensive research has focused on identifying spatial patterns and the underlying drivers physically, biologically, or both. Today this work has shown that the spatial distribution of landscape features can impact gene flow, local adaptation, the flow of energy due to changes in food webs and more (references within With 2019).

With the increase in availability of advanced technologies including remote sensing imagery and data from spatially-distributed environmental sensors both above and below water, researchers are using spatial statistics to discover factors driving spatial patterns as well as what the spatial patterns themselves may represent ecologically. For example, patterns of tree cover may reflect saltwater intrusion into groundwater as sea level rises (Ury et al. 2021); the patch configuration of coastal vegetation may explain patterns in the distribution of organic matter stored in coastal sediments (“blue carbon”, Asplund et al. 2021); and remotely sensed images of the distribution of flowers may provide a path for assessing pollinator resources (Gonzales et al. 2022).

Island Biogeographic and Meta -population/-community Theories

The theory of island biogeography championed by Robert MacArthur and E.O. Wilson (1967) has helped explain the distribution and biodiversity of species in many settings. This theory predicts that larger and less isolated islands will have more species than smaller, isolated islands. This is related to the relationship between the ability of organisms to reach an island (immigrate) balanced by their extinction or emigration rates. The dispersal abilities of organisms and the distance between islands (patches) exert a strong influence on this balance, but extinction or emigration rates are also highly influenced by resource availability on the island. This theory was widely adopted by conservationists who have argued that protected and restored areas should be large, and that fragmentation—even when it does not result in loss of total habitat—should be avoided at all costs. Today we know that even small, isolated patches of habitat play critical roles and have inherent ecological value (Wintle et al. 2019).

Meta-population theory posits that if a species is part of a population that is spread out over a region into multiple subpopulations, then the population is more stable, i.e., less prone to loss from the region (“extirpation”) or loss globally (“extinction”). More recently, this theory has been extended beyond single species. Meta-community theory is focused on multiple scales and how dispersal and spatial interactions from local to regional scales influence ecological process, distributions of whole communities, and their dynamics (Logue et al. 2011). Meta-ecology focuses on the important role that fluxes of all types—water, wind, sediment, organisms—play in ecosystem health and dynamics over time. And these fluxes themselves can regulate other fluxes (Little et al. 2022). For example, the movement of sediment in a riverbed can influence the rates of oxygen flow into the sediments, which impacts the microbial and invertebrate communities that call the river home.

Spatial and Social Dynamics: The Frontier

Nature provides many benefits to people. These ecosystem services are experienced by people locally and therefore, the spatial distribution of ecosystem elements—the ecological components and processes that support ecosystem services—are critically important socially. At the same time, the spatial distribution of humans and their activities influence the status of ecosystem services and often in a way that degrades their provision—a topic that has received a great deal of attention (Metzger et al. 2021). But mapping the provision and flow of ecosystem services is not easy and represents a major area of research. The implications are vast. If we understand how human activities like mining influence the supply and flow of services across space, we can consider new laws that may hold groups accountable for the loss of services. If we understand what ecological features are critical to the provision of services, we may be able to design landscapes to enhance those services and reverse inequities in the winners and losers (Bagstad et al. 2014).

References:

- Asplund, Maria E., et al. (2021). "Dynamics and fate of blue carbon in a mangrove–seagrass seascape: influence of landscape configuration and land-use change." Landscape Ecology 36, 1489-1509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01216-8

- Bagstad, K. J., et al. (2014). From theoretical to actual ecosystem services: mapping beneficiaries and spatial flows in ecosystem service assessments. Ecology and Society 19(2): 64. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06523-190264

- Gonzales, D., et al. (2022). Remote Sensing of Floral Resources for Pollinators–New Horizons From Satellites to Drones. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.869751

- Little, C. J., et al. (2022). Movement with meaning: integrating information into meta-ecology. Oikos, e08892. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08892

- Logue, J.B. and Metacommunity Working Group. (2011). Empirical approaches to metacommunities: a review and comparison with theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26(9), pp.482-491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.04.009

- MacArthur, R. H., & Wilson, E. O. (1967). Island biogeography theory. Princeton, NJ.

- Metzger, J. P., et al. (2021). Considering landscape-level processes in ecosystem service assessments. Science of The Total Environment 796, 149028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149028

- Tilman, D. and Kareiva P. (1997). Spatial ecology: the role of space in population dynamics and interspecific interactions. Princeton University Press.

- Turner, M. G. and Gardner, R.H. (2015). Landscape ecology in theory and practice, 2nd edition. Springer.

- Ury, E. A., et al. (2021). Rapid deforestation of a coastal landscape driven by sea-level rise and extreme events. Ecological Applications 31(5), e02339. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2339

- With, K.A. (2019). Essentials of landscape ecology. Oxford Press.

- Wintle, B.A., et al. (2019). Global synthesis of conservation studies reveals the importance of small habitat patches for biodiversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116(3), 909-914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813051115