Studies have focused on how a person’s positionality—that is their experiences, expectations, social values, personal identities, and world views—influences their research and how, and even when, people engage in group discussions. Sometimes called one’s “standpoint” (Harding 2009), positionality influences what topics are of interest to a person and how they conduct research (Robinson and Wilson 2022). The same can be said for what and how we teach, as well as the comments made by participants during open discussions. Positionality influences the questions asked and the information considered relevant to questions (Jacobson and Mustafa 2019). For these reasons, reflecting on how our identities may be influencing us rather than assuming we can eliminate their effect is useful (Holmes 2020).

Indeed, focusing on and, ideally, revealing one’s positionality prior to group discussions helps each group member and those they interact with place their comments in some context. As members increase their awareness of diverse personal histories and identities, a group or research team can enhance its understanding of divergent views in future discussions. Considering positionality is particularly important to do in the context of sustainability and socio-environmental problems because people’s values and perspectives influence their meanings, creating high levels of ambiguity. SESYNC has stressed the importance of engaging in group activities that can reveal divergent views and help shape a team’s social environment (i.e., how members interact) in positive ways in “Best Practices for Interdisciplinary Team Research: Shaping a Team’s Social Environment.” However, those activities are meant primarily for researchers focused on one specific problem. In classrooms or training settings where people explore a variety of problems over time and individuals work in groups that may change, it is useful to use a more generalized activity.

This lesson introduces one such activity that is most useful when a group meets for the first time; however, groups may wish to revisit it over time. At its core, the activity: 1) challenges participants to reflect on their own positionality and biases; 2) helps increase comfort in discussing difficult topics; and 3) engages learners around a sustainability issue.

- Understand how one’s experiences, socio-cultural status, world views, and other identities influence what is brought to a discussion, a research project, or studies.

- Explore diverse values and views and practice discussing them with respect and care.

- Practice teamwork on an open-ended sustainability issue.

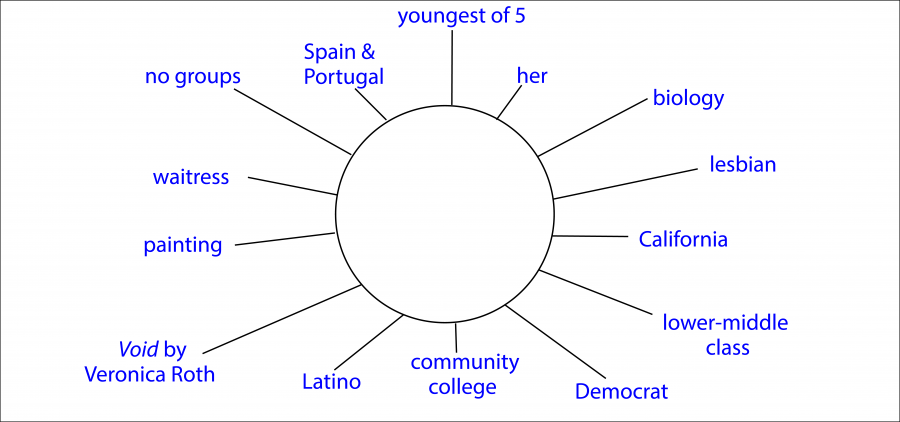

Using a piece of paper or notes on their laptop, ask learners to jot down their personal identities along as many axes as possible (as below, Figure 1). Examples of axes are provided in the numbered list below and in the first PowerPoint slide for this lesson. A response is illustrated also in the PowerPoint slide. Each person should self-identify with respect to 13–15 of the numbered categories, adding above these other categories of their own creation.

| 1. Number in family and birth order 2. Political leaning 3. Religion 4. Potential college major 5. Any group(s) belonged to 6. Last book read that was not assigned 7. Travel experience (e.g., international, local) 8. Where they grew up 9. Introvert/extrovert 10. Past jobs | 11. Talents 12. Race/ethnicity 13. Citizenship 14. Sexual orientation 15. Gender identity 16. Physical or mental limitations (Y/N) 17. Family social class 18. Education level of parents 19. Hobby 20. Body image (+/-) |

This lesson is suitable for a 40-45 minute lesson and requires that in advance learners: 1) complete a writing assignment and bring it with them printed out; and 2) send to the instructor a headshot photo of themselves in color. Instructors should let the students know that these photos will not be shared outside of the class. The lesson assumes a group size of 20 at most; if there are more, the timing for some steps will need adjusting. Instructors should bring to the session: a printed copy of each student photo, tape that will stick to the walls or boards, and enough legal-size or poster-size paper (8.5 x 14”) and markers for each learner. As learners enter the room, each should retrieve their photo.

-

In advance of the session, learners should: submit their photo to the instructor and develop a well-written essay that is at least 200 words long and focused on one environmental problem. It should describe the problem, the causes, social consequences, and actions or policies that could reduce or solve the problem. This essay should be typed, printed out, and brought to the session.

-

(3 min.) Instructors should collect the written essays in some specific order in the room (e.g., left to right) so that they can later distribute them in reverse order (to ensure authors do not receive their own essay).

-

(5 min.) Completing the Hook. Show slide 1 in the PowerPoint and ask learners to complete the Hook in draft form using their own paper or their laptop. The instructor should also complete the hook.

-

(5 min.) Identities Diagrams. Distribute a piece of legal- or poster-size paper and a marker to each learner. Ask learners to reproduce on the paper/poster what they drew in the last step. They should include as many of the identities as they are comfortable sharing with the whole group, and they should leave the center circle empty. After all participants finish, instructors should collect the diagrams, add a unique number to each, and post them on the wall being sure to space them some distance apart.

-

(7 min.) Matching essays to identities. Have learners team up with another person sitting next to them. Hand out the two essays to each team in the reverse order in which you retrieved them, making sure that teams do not get one of their own essays. Teams should then walk around viewing the identity diagrams and find the best match for each of the essays. Once they decide on the best match, they should tape the essay below/next to the diagram and note its unique identity number that the instructor had added earlier.

-

(5 min.) Assumptions. Each team should now jot down assumptions they made with respect to how they matched essays with identity diagrams. Ask them to be thorough.

-

(5 min.) Revealing Identities.

- Ask participants to go to their “Identities Diagram” pages on the wall and tape their photo to them, writing their first name below. If an essay below a person’s diagram is wrong, they should mark it as so.

- Participants whose essays are not correctly associated with their identity diagram should find the correct essay and move it to their diagram.

- All participants should look to see if their matches were correct.

-

(Remaining Time) General Discussion. Bring all the participants together and ask them to reflect on the exercise including sharing some of the assumptions their group discussed as well as how similar/divergent the essays were. Be sure they reflect on their biases and the assumptions they made about participants based on their essays and diagrams.

-

Researcher Positionality – A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research – A New Researcher Guide

Typically called research positionality, reflexivity on one’s background, experiences, and training is strongly encouraged for many humanities and social science researchers. This article is useful because it explains why it’s encouraged and discusses how positionality can influence the approach taken to qualitative research and how researchers can go about understanding their own positionality.

Holmes, A.G.D. (2020). Researcher Positionality – A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research – A New Researcher Guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 8(4), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

-

Social Identity Map: A Reflexivity Tool for Practicing Explicit Positionality in Critical Qualitative Research.

This article is useful because the authors present a “social identity map” that researchers can use to help identify and reflect on their social identity. The map is a type of tool or framework organized by identity categories (e.g., gender, class) that can be filled in and linked hierarchically to other categories. Learners could use this map framework.

Jacobson, D., & Mustafa, N. (2019). Social Identity Map: A Reflexivity Tool for Practicing Explicit Positionality in Critical Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8, 1-12. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1609406919870075